Design thinking: a brave new design world

UX design is an important part of an increasingly blended whole that is human-centric design.

I was typing something into my best friend (ChatGPT) the other day, chiefly for research purposes.

It spat out the usual calling cards of something written by AI. They’re relatively easy to recognise now we’ve become a bit more familiar with the formula (a conclusion for the conclusion; listing of ‘firstly’, ‘secondly’, ‘lastly’; a preponderance for needless repetition, etc).

In my hunt for AI-produced content, I came across a trending discussion that eerily aligned with what I had been noticing around me in both the design and content space. The UX design landscape has started to change, and potentially, for the better.

The change could mean the end of a trendy and once-lucrative career for some. For others, it is an indication of something we’ve known for a while.

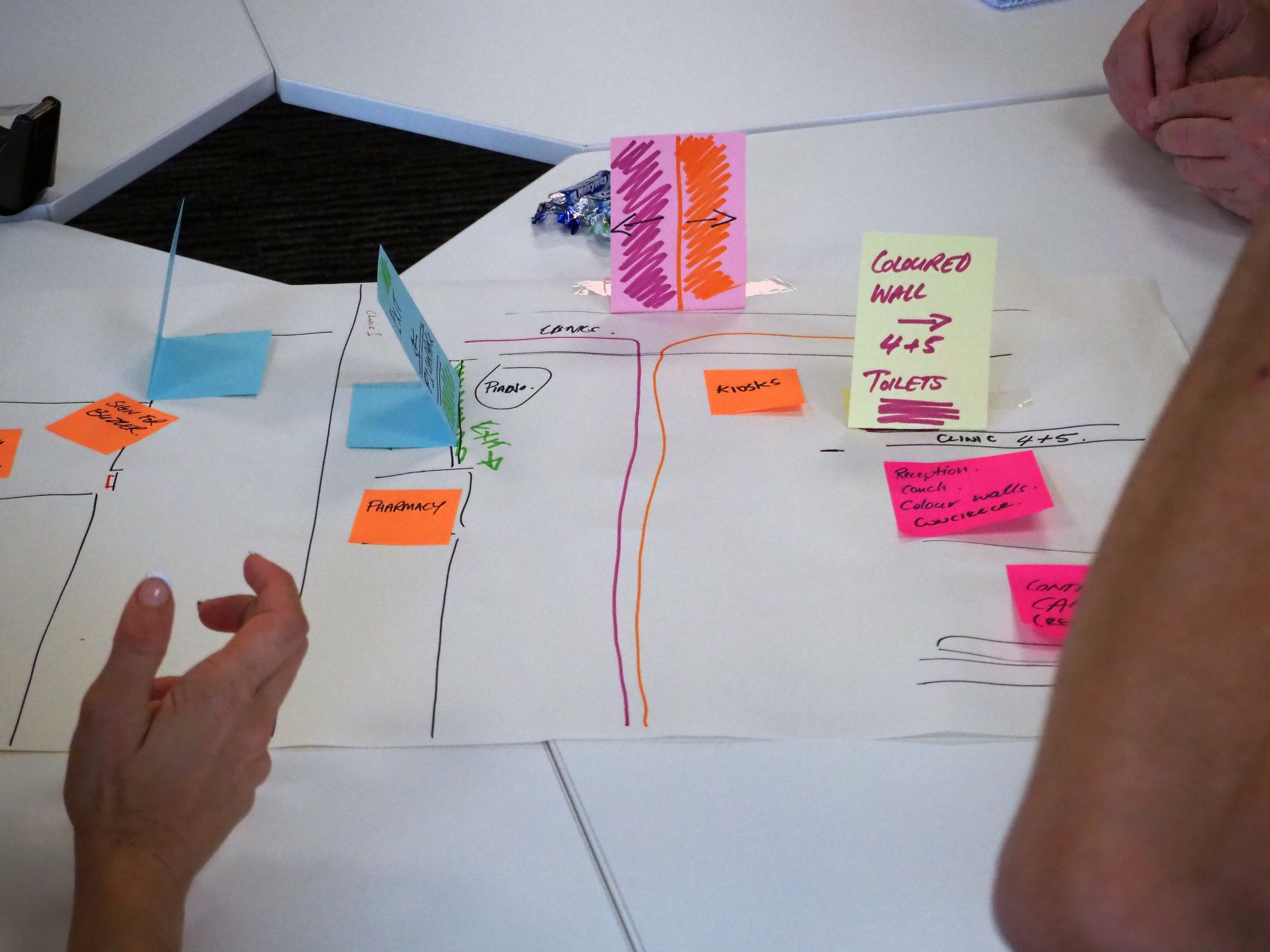

It’s not enough to slap some post-its on a wall and call it user testing. Nor is it enough to reproduce the same digital interface across every project and pray that it works this time.

There’s a whole lot of other thinking, creativity and juggling of skills that needs to go into all design, but particularly wayfinding design.

To meet what’s required to design and sustain a human-centred future, UX is only a fraction of the whole needed to embrace true design thinking.

The shrinking of the UX designer

So, is the strictly UX designer role on the way out?

From a human-centred design perspective, I’m thinking it might be.

Back in what some might characterise as the good old days of UX, 10 years ago the UX business was booming.

Post-It-led user testing was all the rage. Low fidelity wireframes reigned supreme.

Post-Its have their place in the testing realm, but true design thinking calls for human interactivity and creativity

Shortly after was COVID and the job killer it presented for many in the design industry. People lost income and had to stay home, without a clear vision of what their life and career would look like on the other side.

In this flurry of purpose confusion, many turned to UX as a career saviour, with short courses on offering promising a new UX career can be yours in 2 months, maybe even 1 if you rush through it. At the same time, clients started catching on to something the design world was hoping to keep under wraps a while longer: if UX can be taught and learnt in such a short period of time, then something’s gone amiss.

That something would be a severe lack of design curiosity and thinking.

The rise of design thinking

It’s one thing to replicate a pretty touch-screen device that’s been overdone to death. It’s another task entirely to create a digital solution that shapes and improves users’ experiences, blends seamlessly with the built environment, and is both beautiful and accessible.

Design success at this level requires a whole different approach. It calls for curiosity, an explorer's openness, and an iterative conception of progress.

It requires design thinking, which is an entirely different mindset to the churn and burn of replicated design for quick application.

Design thinking places the human experience at the centre of the design process.

It has to deeply comprehend user desires and intentions. It must rigorously question assumptions, including those of the designer and researcher. It has to respond agilely to challenges and develop novel solutions that can be tested and retested for effective improvements in interactivity and engagement.

In this way, the objective of design thinking is to find the answer to potentially very complex questions. Step-by-step, the designer has to empathise with the user’s challenge or distress, define the issue beyond being an organisational or architectural one, and create solutions that address the problem with human-centred solutions.

For the design process to be truly human-centred, it takes a bit more time. It also takes numerous disciplines blending together to help ask the right questions and piece together a solution.

Embracing a blended approach

The role of the UX designer won’t disappear, as some doomsayers are predicting.

UX design is an important part of an increasingly blended whole that is human-centric design.

It needs to join with other people-focused specialities – accessibility, Service Design and Universal Design, to name a few – to form a coordinated, 360-degree approach to design.

Blending different design strategies is good human-centred strategy at work

Creating environments with a genuine people focus will require more than redesigning within the same digital rectangle.

To go beyond mere repeated aesthetics, UX design will need to consider and integrate the intricacies of human behaviour and experience.

If this sounds complicated, it’s because it is. For us though, this makes it all the more worthwhile because we’ve started to see the benefits of this approach. The results are spaces that are more intuitive, accessible, and engaging – both on-screen and in-person.