Our Thinking: Language on Notices

By Michèl Verheem, Partner ID-LAB Global

The other day, I was walking to the studio when a young boy stepped onto the road without looking. It was quite busy, and cars were zooming past.

I had not really been paying attention until I hear a man shout out:

“Please note: stepping onto the road without paying attention to the particular traffic circumstances, the amount of traffic, the frequency of said traffic, and the velocity of the vehicles making up the traffic might result in a collision between a pedestrian and a vehicle, possibly resulting in, at minimum, some sort of injury, most likely for the pedestrian. We recommend not stepping out in front of moving vehicles.”

I immediately looked up and saw the young boy jump back onto the footpath. It was clear that the man saved the boy's life.

This, of course, did not happen this way. What did happen is that I heard a man shout out:

“Watch Out!” Upon hearing the cry, the young boy jumped back onto the footpath. The boy was shaken up a bit but saved (although, looking at his shocked mum, I am not sure how ‘safe’ he really was….). The ‘Please note’ message I made up. I did this because I want to address how we can make instructions clearer, and more useful.

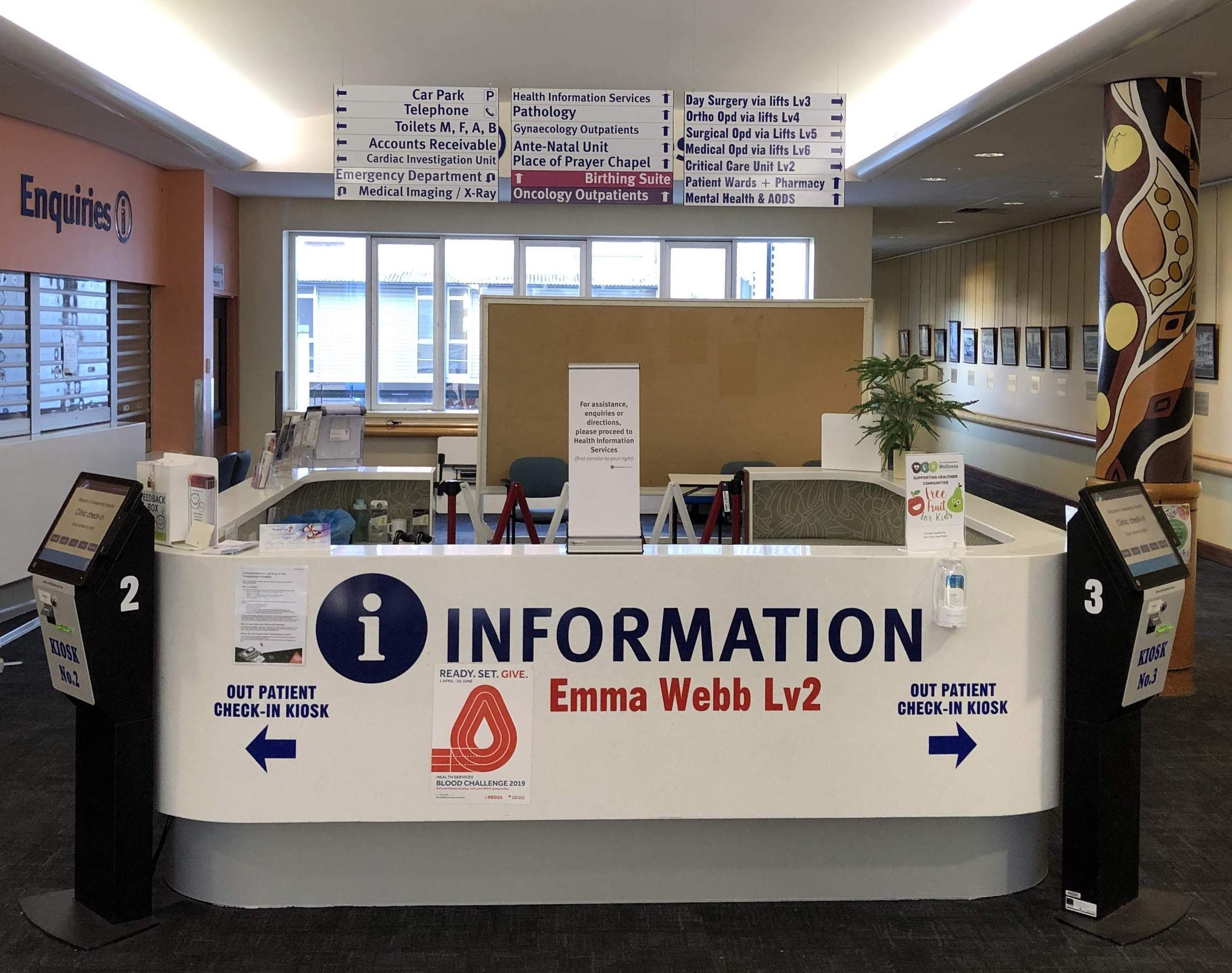

When we start work on a ‘brownfield’ site, one of the most striking observations in almost all projects is a large amount of signage everywhere (because when someone complains, you apparently simply place another panel with an arrow on the wall). But even more than the number of signs is the huge amount of – sometimes very wordy – instructions, both formal ones and informal ones.

Some of the wordy notices, possibly, are so wordy because the writer thinks that the instruction should be ‘packaged’, wrapped up like an elaborate present. They mix a few formal words and sentence constructions with lovely friendliness and a ‘thank you for your consideration’ at the end. Others try to sound like – or are in fact – legal language.

I came across an example of the friendly notice the other day, in the toilets of a public hospital. There were two A4 papers stuck to the walls, next to the washbasins, and just above a cardboard box on the ground.

The first notice said:

“Take the time to dispose used hand towels in the waste box provided”, the second one:

“ATTENTION Paper hand towels are not to be flushed in the toilet bowl. Frequent blockage of the toilet is due to this practice. Please dispose hand towels in the prescribed recycle bins below the hand basins. Thank you for your cooperation.”

I read them while washing my hands and really had to read them twice to fully comprehend what the message was that was hidden in this blur of words.

My guess is that they have had some problems with their toilets and that they want people to throw towels in the bin, not in the toilet.

Maybe it is worth distilling the messages from the two original notices, to see how we could improve the message. Let’s start with the word ATTENTION. It was in capitals (like the rest of the notice). Bold and underlined. It needed to be seen, obviously.

Then came the useful information that the ‘paper hand towels’ that were provided next to the hand basin should not be ‘flushed in the toilet bowl’. Not just the toilet as a concept, but the toilet bowl, to be exact. And not any of the other provided towels, only the paper hand towels.

The reason for this is explained in the second paragraph of this epistle. In even more flowery language. As a language purist, I was flabbergasted by this second part. Is blockage caused by NOT flushing paper hand towels in the toilet bowl?

And then what I consider to be the most important part of the notice: the instruction of how to behave.

It starts, like all instructions in Australia, with the required ‘Please’. It continues with describing in which bin EXACTLY (the prescribed one, not just any ol’ bin hanging around this toilet block) and where said bin is located (for the people who do not recognise a bin when they see one). But what happened to the ‘waste box’ from the first notice? Had this gotten lost amongst the large number of bins in the toilets?

I was glad that there was an acknowledgement of my effort to co-operate. It had been quite a task.

How can this be different?

We’ve all heard ‘Less is More’; a phrase adopted in 1947 by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. It is not as simple as that. Following Mies’ paradigm, ‘nothing’ would be the ultimate, infinite, quantity. At ID-LAB we work according to a principle expressed (although not quite verbatim) by Albert Einstein in 1933: “Everything should be as simple as it can be, but not simpler”, at ID-LAB also described as: “Cut the Crap, Keep the Quality”.

Most of the time a message can be clearer with fewer words. Way fewer.

Our recommendation for this simple message would be:

As Albert said: “Everything should be as simple as it can be, but not simpler”.